Today I finished an adventure that I had started out on just a mere 24 hours or

five months earlier:

Okamiden.

My initial apprehension towards Okamiden rapidly faded as I began to get into

the game and realize that in it’s complexity it was far more than just a scaled

down rehash of the seminal PS2 Okami. From combat, to brush strokes, to

atmosphere and plotting the game has nearly everything that it’s big brother

has.

Gameplay

My initial impression dwelt heavily on Okami’s scaled down gameplay at it’s lack

of features. I now have to eat these words. Although the button-mashing aspects

of combat are scaled down to just mashing A to attack, the ease of using brush

strokes on the DS makes the spirit brush an integral component of late-game

combat. As I began collecting slicing, lightening, fire, and wind strokes I soon

found myself combining them into effective combos: wind to knock an opponent on

the ground, rain or lightening to slow and trap them, then close in with a

couple of bombs and basic attacks. I would say that by the end of Okamiden it

had the combative depth of Okami.

Dungeons were likewise exemplar. Puzzles made liberal use of companions special

abilities and combinations of brush strokes to activate devises. I found myself

taking my time in many of these places to really explore all the rooms, solve

the extra puzzles and pick up every last scrap of artwork I could find. I don’t

think I have so thoroughly immersed myself in the exploration aspects of a

dungeon crawl since Ocarina of Time.

Aesthetics & Plotting

Okamiden is gorgeous and I am rather surprised that the aesthetics of Okami

could scaled down so perfectly to fit onto the DS’s small screen. Yet, here it

is completing with music, sounds and tantalizing natural scenes.

Okami suffered one issue. It jumped the

shark in its

plotting. The early gameplay introduces eight-headed dragon Orochi and for the

large part of the tale we believe that we are somehow fighting against this

beast. Yet, we defeat him two thirds of the way through the game and are

suddenly a new demon turning the progression of the story completely on it’s

head. The result is a feeling that the later half of the game had been rushed

and lacks the detail of the first portion of the game. The ending seems a tacked

on after-story to the quest to lift Orochi’s curse.

Okamiden, on the other hand, feels like a much more complete narrative. The

major plot turns are well foreshadowed and we expect these surprises – Kurow’s

betrayal and the appearance of Akuro make sense from a narrative perspective.

I feel that Okamiden is a complete adventure title. Unlike the DS Zelda titles

which I think attempt to be minor iterations in the overall Zelda lineup –

Okamiden simply feels like a full fledge title and not a scaled down hand-held

port of it’s predecessor. I hope that it sees some good success on the handheld

platform and look forward to the continuation of this franchise. Kuni’s tale

deserves to be told.

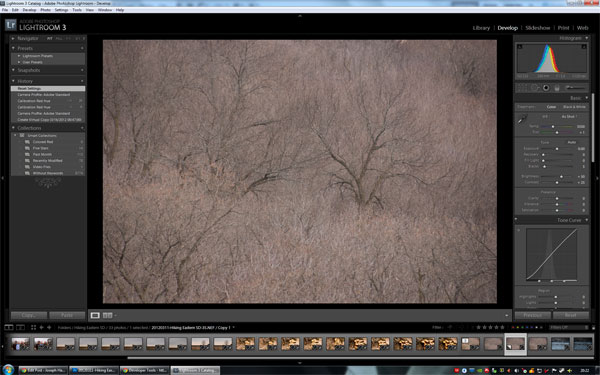

Eureka! I’ve solved yet another odd puzzle of digital photography: easily

making your RAW file look like what you see on your Nikon’s LCD screen.

Perhaps you have just made the leap from shooting with JPEGs to shooting with

RAW. You’ve already read up on the various deficiencies of JPEGS: compression,

loss of color data, difficulty of editing and the many advantages of RAW:

ability to easily manipulate midtones, white balance and apply color filters in

post production. Happily, you start shooting in RAW but there is a problem. The

unprocessed photos lack the pop and vividness of your old JPEGs.

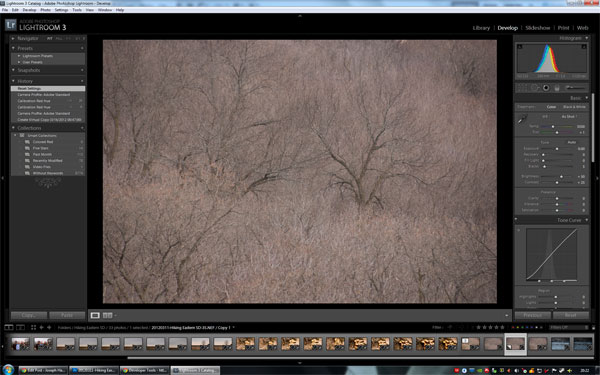

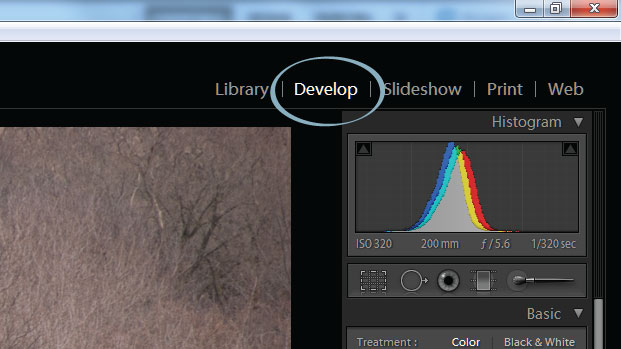

When you first open your RAW file in ACR or Lightroom there is a brief flicker

as your various in-camera settings (saturation, warmth filters, vividness) are

stripped away leaving you with a rather dull looking low-contrast image. This

is because your camera saves a small JPEG thumbnail to showcase on it’s LCD

monitor. This thumbnail contains all the post-processing features that your

camera does on JPEGs to make them pop for the novice user.

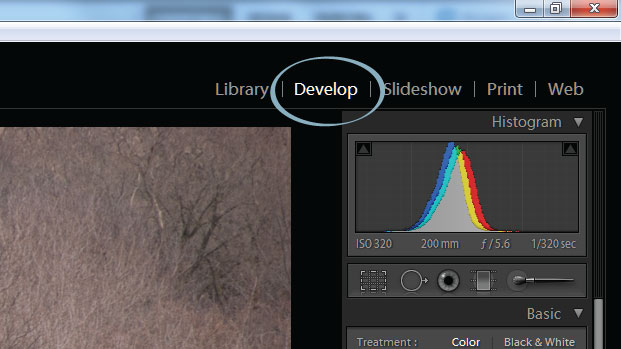

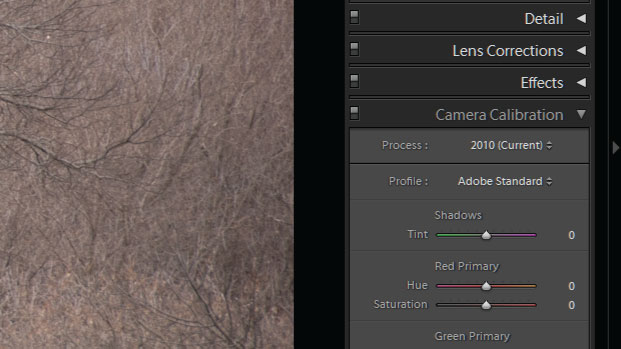

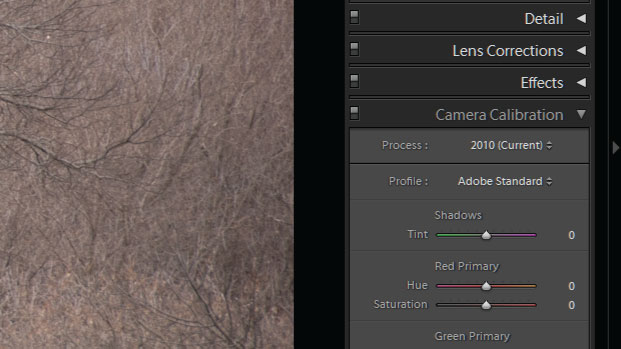

The color calibrated image is on the left while the Adobe Standard is on the

right. Note the added sharpness and warmth that calibration brings to the left

image.

I used to spend hours messing around with the sliders in Lightroom just trying

to recreate the same vivid colors that I saw on my camera’s LCD monitor and all

the while cursing Lightroom, Picasa, or Photoshop for gimping an otherwise

perfect shot. Only last week did I discover the easy, automated method in

Lightroom 3 to bring back the beauty camera’s in-house processing performs.

This method is camera calibration. Simply follow these steps:

Open Lightroom 3 and select the photo you want to restore to your camera’s

settings.

Click on the Develop

tab on the upper-right hand corner.

Click on the Develop

tab on the upper-right hand corner.

Below the histogram at

the very bottom of the right toolbar is the Camera Calibration toolset

Below the histogram at

the very bottom of the right toolbar is the Camera Calibration toolset

The Camera Calibration allows for manual adjustment of the Red, Green, and Blue

values of the image as well as the tinting of shadows. You will find something

odd about this tool, namely: adjusting sliders in the Camera Calibration tool

will not adjust the Hue/Saturation Sliders or Tone Curve of the image but

rather defines a new “starting point” for post processing the image.

While the sliders can be used to make adjustments, the easiest method is to use

the presets under the profile drop-down which for my camera (a Nikon d80) gives

the options of :

- List item

- ACR 4.4 and ACR 3.6 (this is Photoshop’s defaults)

- Adobe Standard (this is the ugly, bland default for lightroom)

- Camera D2X Mode 1, Mode 2, and Mode 3 (more on these below)

- Landscape

- Neutral

- Portrait

- Standard

- Vivid

The Adobe Standard which comes pre-selected for you also happens to be the

blandest of all the profile options. I suggest trying one of the Camera Modes,

one of which will most certainly closely match with the image your camera

displays on it’s LCD monitor. My favorite is Color Mode 3 for it’s warmth and

vividness when shooting nature shots, but it can be too warm and too vivid for

portraiture or indoor shots and so this gives a good opportunity for overriding

my camera settings to select Portrait or Camera Mode 1 on the

rare occasions that I am shooting an event. The Vivid profile is also fairly

interesting, but I would suggest using it on a case-by-case basis since it

seems to blow-out already bright photos.

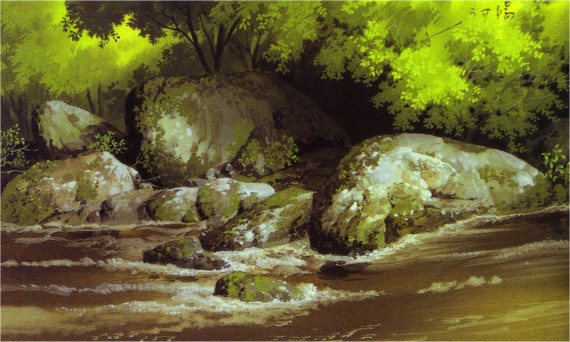

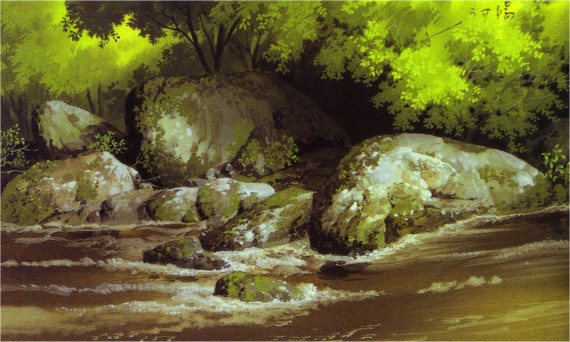

It was my luck that The Secret World of Arrietty came to Sioux Falls. This is

my first Ghibli film that I could see in its proper setting: the big screen and

I must say that it was a spectacular treat for the eyes, replete with stunning

backgrounds and gracefully animated characters who play out yet another

fantastical story. While Arrietty will probably not be my most favorite Studio

Ghibli film, it does possess the wit, charm and magic that I expect from the

creators of Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, and Princess Mononoke.

It’s only real lack is in it’s pacing, which seems much slower than past fare

and for some may be too slow.

I happened to watch Spirited Away the day after seeing Arrietty and it

occurred to me how much sense of atmosphere Ghibli creates in their films

through the deep sense of place and connection that chracters have with the

environment that they occupy. Ghibli certainly pays very close attention to the

details in it’s stories and illustrations and I think that this sense of

environment is just one example of stroytelling that makes their films so

tremendously delightful.

Environment in story informs the characters and plot, or at least it should if

the author is paying any attention to their setting. A character who is actually

living in their world will face the unique limitations that their environment

creates – their culture, actions, and life will all be informed by this

setting. Ghibli films realize this reality in a way that so many other films

simply ignore. Their worlds draw upon the ambient emotions that nature’s many

forms (violence, tempered, serene, and sublime) create in the human psyche. Let

me take a quick glance at a few Ghibli films and illustrate how this plays out:

Princess Mononoke

The atmosphere of Mononoke drips of the time when the wilds were an alien and

unforgiving place for mankind. Early on in the film we see the difficulties that

civilization has sought to overcome: the danger of predatory animals (Moro), the

difficulty in navigating the wilds (the muddy and treacherous caravan trips),

and deadly weather. Yet, nature still possesses a sense of serenity. The Emishii

peoples seem to live a harmonious existence with nature as does San. The

characters who find nature the most brutal are the ones who act the hardest to

work contrary to their environment. Overall, the scenes create an atmosphere

that mimics the internal difficulties of each scenes principal characters. For

the caravaners the woods is a dangerous, frightful place but in the hands of

Ashitaka the woods becomes a land of delightful and helpful spirits –

the differences not in the woods, but in how the characters approaches dealing

with their sense of place in the natural world.

Spirited Away

Since Spirited Away takes place in a bath house and not the wilds we see a

very different approach to place. The bath house of Yubaba is a fusion of

Japanese and Chinese aesthetics that exaggerates the more gaudi elements of

Chinese style and completely abandons Buddhist simplicity in everything but its

depictions of the natural world. The bath house is simply an extension of

Yubaba, who is a greedy and gluttonous crone. We see these characteristics not

only in her employees but reflected back to them by Noh-face who absorbs the

essence of the place as he stumbles about eating the staff and flinging gold

about. Not until he disgorges the filth of the bath house can he go back to his

simpleness.

The Secret World of Arrietty

The world of the borrowers takes on a much more realistic charm that lies less

in the fantastical elements as much as trying to showcase how the borrowers

would interact with their gargantuan environment. Arrietty’s family lives in the

walls of houses where they make their way about using ropes, nail staircases,

and simple free-climbing techniques in an adventurous method that reminds me of

real-world caving. They “borrow” from their environment as they take only what

they need from the Beans who they both live beside and in fear of. I think in

Arrietty we see a kind of modern Emishii where their lifestyle nurtures a kind

of connectedness to their environment that emphasizes a sense of propriety over

taking only what is needed while leaving the superficial (the gaudy playhouse)

behind.

Click on the Develop

tab on the upper-right hand corner.

Click on the Develop

tab on the upper-right hand corner. Below the histogram at

the very bottom of the right toolbar is the Camera Calibration toolset

Below the histogram at

the very bottom of the right toolbar is the Camera Calibration toolset