I recently attended a showing of The Iron Lady

at the bequest of my girlfriend. I was

initially reluctant to see such a production – not because of some distaste for

a biopic of Margaret Thatcher, but because I feared that it would just be a

simple film riding on the coattails of last year’s The King’s

Speech.

The King’s Speech won four Oscars last year and for a very good reason. It is

an eloquently produced work illustrating the changing political climate of

Britain as it transitioned from the Victorian into modern times. Yet, here we

are one year latter with yet another film about yet another British ruler. How

can I not consider this a grab on the prior work’s success?

Nevertheless, I was surprised to find that The Iron Lady can stand upon it’s

own accord. I knew little of Margaret Thatcher going into the film, save that

she was an influential Conservative party politician in Brittan through the

seventies and prime minister through the eighties. Folks still talked and argued

about her influence when I went to Oxford just a few year’s back. She seems to

be a rather reviled women and yet surprisingly influential on British society.

The Iron Lady showcases a kind of highlight reel of Thatcher’s life. A few

scenes from before her entrance into politics, her campaign for leadership of

her party, a handful of NRA inspired terrorist attacks, the Falkland’s war, and

her eventually fall from authority. Overall these scenes are rather touching and

masterfully performed by Meryl Streep.

Yet, he film spends it’s time predominately dealing with her current dementia.

This is surprising since there is such a wealth of material from her actual life

as the first female Prime Minister of Brittan and this dementia deals so very

much with her late husband who is scarcely found in her historical remembrances.

My initial response to the film was delight. As a biopic, I walked away rather

inspired to hop online and research more about Thatcher. As the days pass

however, I find myself more and more caught up in the film’s narrative failures

in a way that I did not feel with The King’s Speech. Indeed, whereas I might

go back in a few years time and enjoy The King’s Speech again – I do not

think I shall do so with the The Iron Lady.

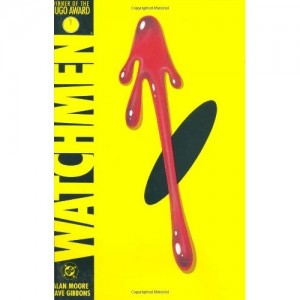

I wrote a short review about Watchmen back when the film came out

in theaters and while I have read the book, I wish to address the film in

particular. I will be revealing a lot of the plot devices in this one, so if you

haven’t had the chance to read or watch the film, I say skip this and come back

once you have.

Watchmen is to Super Hero films what Neitzche is to Nihilism. It would seem at

first that Watchmen is just a grittier version of the Super Hero genre. Filled

with anti-heroes, sex, violence and the dynamics of less-than-perfect humanity,

the work portrays itself as being a critique of Super Hero romanticism.This may

be true in the graphic novel, yet the film takes this concept slightly further

in its alterations to the ending.

Through the earlier sections of the film we are introduced to a post-Neitzchian

society. The ambitions of man are kept in checked by a careful balance of

political power. Russia and the USA have the bomb, but the USA has Dr. Manhattan

– a superman with the power to see through time, cause people to explode, and

any number of other powers. This superman is Neitzche’s ubermensch. Yet, his

mastery is bent to the futile intrigues of his surroundings and he has become

disconnected with mankind and he begins to see past man and into their empty,

futile attempts to placate fate. The greater part of society is now living

post-god in which man exists not in fear of some retributive all-powerful deity,

but must only fear the retribution of his fellow man. Such fear was kept in

check for a while by the threat of the vigilante”Watchmen,” who superseded the

law authority to enact retributive justice upon lawbreakers.

Here is that central theme of Watchmen: is there any justice at all? Certainly

it seems in the text that the justice of the political fails to address the

people’s needs to see justice served. Society is rank with villainies such as

robberies, murders, rapes, and muggings. The Watchmen, more or less, are also

not the answer to justice as each of them pursues their own particular view of

justice which in the end is merely self-serving. Heroes such as Silk Spectre or

the Comedian are merely in it for the fame and power and Nite Owl is fueled by a

sense of wishy-washy moralism that exists more out of expediency than

the virtuous determination we see among Super Heroes. We see fellows trying to

rise up to the status of Nietzsche superman. They establish these self-made

virtues but cannot follow through with them, and so fall back into the line of

the society of men. Watchmen’s society is thus that of a nihilism, not

Nietzsche’s self-determinant society of supermen and the answer in Watchmen is

not that of the existentialist, but of the necessity of re-establishing God in

order to keep man in line.

Look at the film’s end. Viedt’s mastermind plot is to subvert nuclear war by

attacking first. He nukes all of the super power’s city centers using weapons

designed to look like Dr. Manhattan’s unique radioactive signature. These

attacks force society to re-evaluate itself and come together in the realization

that they have much larger threat to mankind: Dr. Manhattan. Dr. Manhattan is

thus God incarnate, a new kind of messiah who saves not through sacrificing

himself, but by sacrificing the rest of the world. This is the vengeful God of

the old testament who will suffer none of the squabbles of humanity. By

providing the world with this new-found maker of miracles (or ought I say

plagues), Viedt reveals that God is very much alive and he is a giant blue man.

Dr. Manhattan, fed up with meaningless bickering of mankind, leaves earth for

the sterility of the heavens where Viedt can assure the people of earth he is

watching over them carefully. Again that father-figure is restored into culture

and the nihilist society is resolved not by truth but by the re-establishment of

a great lie.

Rorschach, however, is our true super hero. The man who is fighting for truth

and very much believes in justice. Viedt, and ultimately Nite Owl believe

in alleviating suffering not the upholding of an abstraction like justice. In

the world of the Watchmen there is no place for a man who truly believes that

there is justice. Such a man would be absurd or “nuts” as Rorschach is referred

to by his fellow super heroes. Yet if we superimposed Batman, Superman,

Spiderman or any other superhero into this space they to would be seen as

hopelessly naive at first, and if the hopelessness of society didn’t drive them

to the madness of Rorschach then they would be rather unbelievable. No,

Rorschach is representative of a desire for a just world. He wants a world that

is more than just nice, where people are pleasant and freed from suffering. He

wants a world were justice is seen to and the people virtuous. Such a man cannot

live long in the mockery that Viedt creates: the world of lies that we live in

as we tell ourselves that all is right and just in the world. In the end,

Rorschach is killed by Dr. Manhattan because there is no place for a just man in

such a world.